The Tower of Flints, patched unevenly with black ivy, arose like a mutilated finger from among the fists of knuckled masonry and pointed blasphemously at heaven. At night the owls made of it an echoing throat; by day it stood voiceless and cast its long shadow.

Mervyn Peake, Titus Groan

My interest in Kinugawa Onsen—the hot springs resort on the river of angry demons, as its name might translate—was first sparked when, not so long ago, I stumbled across the following article, which appeared in The Times on the very last day of 2005.

Monuments to ugliness and the triumph of cash over culture

From Leo Lewis in Tokyo

JAPAN’S most senior urban planning expert, who decries almost every city in his country as “hideous”, has devoted two years to drawing up a list of the nation’s most repulsive places.

Shigeru Itou’s damning report Ugly Japan is specifically designed to provoke national outcry, and, he hopes, become the centrepiece of a drive to make the country more beautiful. He has enlisted to his cause a panel of architecture gurus, designers, sculptors and Japan’s top civil engineers — his seniority and renown also grant him direct access to the highest ranks of government.

Within weeks of becoming Prime Minister, Junichiro Koizumi called on Mr Itou, an emeritus professor of Tokyo University, and put him in charge of a Cabinet office panel to study a “Japan beauty renaissance” to undo some of the monstrosities of the past 60 years. Professor Itou is careful not to single out particular buildings as ugly, believing that his report is only useful if it deals with “objective ugliness, not subjective dislikes”. He does, however, reserve a private judgment on the glittering steel and glass tower of Roppongi Hills, one of Tokyo’s most famous new landmarks and a structure which he thinks “resembles an old Russian woman’s backside”.

In an exclusive interview with The Times, Professor Itou revealed the contents of his forthcoming “list of the loathsome”, in which modern shopping centres and decrepit “love hotels” are lambasted along with ancient imperial gardens and tree-lined avenues in Hiroshima. But the ultimate accolade in the professor’s reverse tourist guide goes to the Nihombashi bridge in the heart of Tokyo. The ornate structure which was constructed in the 17th century, is charged with history and cultural significance — not only is it the point from which all distances to the capital are measured, but the commerce created by the bridge was what turned the old city of Edo into the country’s most important city. Unfortunately, urban planners preparing the city for the 1964 Olympic Games built an eight-lane motorway flyover just a few metres above this historic landmark, engulfing it with steel support pillars and denying the bridge any daylight at all.

“It was about showing that Japan was no longer poor. Beauty meant nothing to Japan then,” said Professor Itou. Having the ear of Mr Koizumi has evidently had an effect — after a meeting with the professor two days ago, the Prime Minister has asked for a study into moving the vast motorway and “opening Nihombashi to the sky so we can enjoy riverside walks”.

Runners-up in the 70-strong cavalcade of eyesores include a shopping arcade in the former coal mining town of Omuta, in which every shop has been boarded up, and a site in Yashio where Yakuza gangsters have muscled their way into a small residential street and established an industrial waste dump.

Near the top of the list is the valley of Kinugawa, a once stunning hot-spring town where, in the 19th century, the wealthiest city dwellers would escape the stench of the summer. In the booming 1970s scores of hotels were built astride the valley — immediately destroying its appeal. When everyone stopped visiting, the hotels went bust and now stand as crumbling testament to the awfulness of bubble-era construction.

BIGGEST EYESORES

1 Nihombashi Bridge and the flyover from hell

2 Kawaguchi Station the most chaotic bicycle park in Japan

3 Kinugawa the ghost town the bubble built

4 Omuta city the shopping arcade of a thousand bankruptcies

5 Hamarikyu Gardens built for an emperor, but collects all the flotsam in Tokyo Bay

6 Fuefuki discount shopping centre the most garish in all Japan

7 Utsunomiya station the nest of the loan sharks

8 Akasaka ghost house not a square inch without graffiti

9 Shibuya river where even the water rats fear to tread

10 Yashio the industrial dump next door

Kinugawa the ghost town the bubble built? This I had to see. What follows, then, is a composite account of four separate visits between mid-March and mid-May: two solo day trips by car, one day trip by train in the company of an old friend from the UK, and finally one solo weekend trip, with every visit yielding another patina of decay. (I plan eventually to bring you tales of all of Professor Ito’s top 10 eyesores. Remember folks, I visit these places so you don’t have to.)

************

Kinugawa Onsen is located north by northwest of Tokyo some two hours by train and anywhere between two and four hours by car. Lining the sides of its eponymous river, it occupies the foothills of the southwestern corner of Nikko City, most famous for the World Heritage Site of the shrines and temples of Nikko itself, from which it lies only a few kilometers distant.

On a country backroad, heading to the onsen resort for the first time, I was distracted just inside the city limits by a concrete crenellation that promised the frisson of dereliction and proved premonitory of what was to come.

The sign of the love hotel Don Quixote promises a sophisticated mood at an affordable price. Love hotels generally have a two-tier pricing system: one lower price for a “rest”, one higher price, often double that of a rest, for a “stay”. Don Quixote charged Y3,000 (roughly $35) for a rest; the sign’s shards no longer reveal what a stay would once have cost.

As I eased myself between the ropes slung across the entrance, I was met by a muted but insistent drumming, which, adding to the air of woeful foreboding, took a moment to identify—it was meltwater from the latest snow of the season ever recorded hereabouts cascading off the eaves of the cottages.

Don Quixote had been a conventional love hotel of the rural and semi-rural breed, a semicircle of bungalows with attached carports, their curtains now in shreds.

One of the chalets had lost its window, now a gaping maw.

Gingerly, I peered in and had my breath taken away by the ancient TV set

and the gaudy furnishings.

The conclusion to be drawn from this, and from the advanced state of collapse of some of the buildings,

was evident: Don Quixote had seen its last love made sometime around 1980, three decades earlier.

Abandoned love hotels like Don Quixote are fascinating, I think, for three reasons. First, of all of Japan’s manifold varieties of wreck—amusement parks, pachinko parlors, and sanatoria, houses, restaurants, and apartment blocks, factories, mines, and railway lines—they are the most poignant, places that once celebrated life in the act of (at least potential) procreation, however frivolous or humdrum or guilt-ridden, now mausoleums of past acts of intercourse. There must be many people, now approaching middle age, who owe their very existence to the services of Don Quixote. Indeed, Sarah Chaplin, in Japanese Love Hotels: A Cultural History, relates that “one researcher calculates that half of all sex in Japan takes place in a love hotel, and that a large proportion of the country’s offspring was therefore conceived in one”.

Second, Japan’s abandoned love hotels are one of the few places on the planet the privileged intruder can be rewarded with instant travel so far back in time, back in this case all the way to the seventies, the decade that taste forgot. In the West, a place like Don Quixote, no matter how remote, would have succumbed to vandalism and arson within years, if not months, of closure, and outside the West only Japan had attained the status of a developed nation by 1970 or even 1980, so only in Japan, scattered here and there in dusty byways across the land, can the explorer unearth these relics of an age almost as remote, to our era of iPads and Twitter and YouTube, as the lives of eminent Victorians must have seemed to sixties swingers.

Finally, Don Quixote and its ilk are simply the advance party for the battalions of clamorous ruin that will engulf much of Japan outside of its conurbations over the coming half-century.

From still-spruce signs advertising other love hotels along this short stretch of road I had concluded that Don Quixote had fallen victim to its own private catastrophe; further investigation, however, showed this not to be the case.

Set back on a less trafficked lane nestled Hotel Dreamy.

Hotel Dreamy had met its demise in the much more immediate past. Note the prices outside the dreamy cabin and dreamy carport: Y2,500 for a rest and Y5,000 for a stay. Evil deflation is setting in.

Not far up the lane was a turn-off to Hotel Crown, now hidden deep within a ramshackle conifer plantation.

An oasis of rest, promised the sign. Across fallen trunks from the neglected plantation that lay strewn across the approach road, I picked my way into the compound. The first bungalow whose door I tried creaked open and I tiptoed inside.

Opening the door to the bedroom from the hallway, with the door half ajar the doorknob came free in my hand and I was assailed by darkness, startling in its utterness, and the reek of mold. Briefly paralyzed, I beat a retreat.

Of the five love hotels that once dotted the neighborhood (Don Quixote stands next to another, Hotel Century, which must have perished around the same time), only one remains in operation: Hotel Asaka.

Despite the survivor benefits that one might expect to accrue in a normal business environment, Hotel Asaka, further ravaged by deflation, charges Y2,500 for a rest and only Y4,000 for a stay.

There has been a flurry of Western interest in investment in (urban) love hotels of late: see, for instance this credulous article and this one, tinged with disappointment. Don Quixote, I hope, will serve for some as awful warning against such folly. It doesn’t take a demographic or financial genius to divine what befell this knot of love hotels: they, like all love hotels, catered to mostly to the 20-35 age bracket, who largely live at home. Nikko’s population has fallen dramatically, from just shy of 100,000 in 1995 to below 90,000 today, while the neighboring town of Shioya, which Don Quixote and its cousins border, has seen its population ebb away from over 15,000 in 1985 to around 12,500 now. The pace of population decline for 20-35 year olds has naturally been much more precipitous. As Nikko goes, so goes Japan: while in 2005 there were 1.97mn Japanese aged 35, there were only 1.30mn aged 20. While there were 23.7mn aged between 21 and 35, there were 17.9mn aged between six and 20 (the future market), almost a quarter fewer. It is also at least plausible that the increasing affordability of urban accommodation, occasioned by plunging land prices, will further spur home-made love-making. Feel like investing in a love hotel fund now?

************

The waters at Kinugawa were first discovered on the west bank of the river in 1691, and for a century and a half they were reserved exclusively for the use of daimyo lords on pilgrimages to Nikko and for the Buddhist priests of Nikko’s temples. With the overthrow of the feudal order at the Meiji Restoration,the waters were opened up to commoners. Springs were discovered on the east bank in 1869 and later, a hydroelectric plant lowered the level of the river, revealing yet more springs. In 1927, Taki Onsen on the west bank and Fujiwara Onsen on the east subsumed their separate identities in a renamed Kinugawa Onsen.

With the advent of mass tourism in the years of turbocharged growth in the 1950s and 1960s, Kinugawa prospered, becoming known alongside the resort towns of Atami and Hakone as one of Tokyo’s okuzashiki, “back reception room” retreats. In the 1970s and 1980s, the old inns were torn down and replaced with concrete behemoths of hotels, with the crescendo of construction coming to an abrupt halt with the bursting of the Bubble in 1990. Hotels now flank the gorge so densely that the five bridges across the river are almost the only places that afford a view of it. This is the gorge from downriver, looking north.

And the gorge from midriver, looking north again.

Annual visitor numbers peaked at 3.4mn in 1993, the year in which the Tobu World Square theme park—which we’ll come to later—opened, and then declined remorselessly for a decade, before leveling out for a while at around 2.3mn in 2003, before slumping again in the recent recession. Kinugawa, like every onsen resort in the land, was afflicted by two structural woes: the parlous state of the economy and changing tastes in tourism, as shudan ryoko, group trips with colleagues, fell definitively out of fashion and were usurped by more intimate holidays spent with family or friends.

Kinugawa has also been plagued by problems more peculiarly its own, though. As the hotels grew larger and spread north and south upriver and down, the resort lost a central locus, and with that the bustle and carnival that an onsen town, in Japanese eyes, should have. Respondents to a 2006 survey by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport (MLIT) bemoaned its lack of vitality, the emptiness of its streets, and the abundance of its vacant lots and stores. In a 2002 Nikkei assessment by professionals of the appeal of 66 onsen resorts nationwide, Kinugawa ranked a lowly 53rd. While the experts praised its natural setting and convenience for nearby tourist honeypots, they damned it for its lack of cultural facilities and events and the blandness of its hotels and cuisine. Kinugawa’s own hoteliers, surveyed by the MLIT, saw the resort’s strengths as the ease of access from Tokyo and its nationwide name-recognition but were aware it was missing an onsen resort atmosphere, had a hemmed-in feel resulting from the absence of riverside walks and paths into the mountains, and suffered from the fading appeal of the theme parks and other tourist attractions in the vicinity.

************

One of Kinugawa’s attempts in recent years to rebrand itself has been the creation of an “image character”, Kinuta, derived—I guess—from the “angry demon” of “angry demon river” and the first half of “Taro”, the stereotypical Japanese boy’s name.

This Kinuta, presented by the local neighborhood and merchants’ associations, lolls in front of the station.

This one, too, guards the station, presented by the local Rotary Club in 2003 on the occasion of its 40th anniversary.

The plaque below carries a heartfelt message.

We invest in the figure of this demon, standing proud, so powerfully built and full of life, our hopes that Kinugawa Onsen thrives.

We want Kinuta to become the mascot of Kinugawa, beloved by all, so we decided on a child demon, with cuteness within strength.

We gave him a rod of iron, in line with the proverb 鬼に金棒, to reflect our hopes that Kinugawa Onsen will become, undisputed, the most wonderful onsen resort in all Japan.

(The proverb literally translates as “give a demon a rod of iron”, meaning to make a strong person [or team or town] even stronger.)

Kinuta is to be found all over town; here he pops up, recumbent, in a remote parking lot used by almost no one.

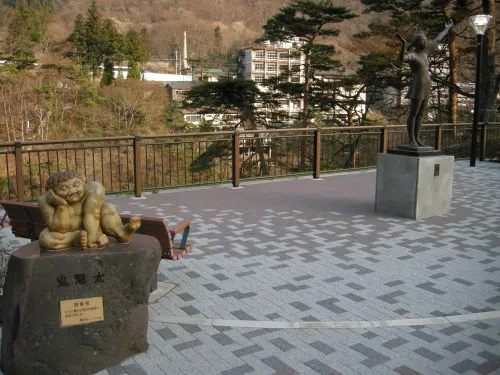

This next Kinuta, donated by a private individual in 2008, leers at the untitled statue of a girl with arms held aloft in hope. At least, I hope it’s hope.

“You and me and the devil make three”, I started murmuring to the girl.

Go to sleep little babe,

Go to sleep little babe,

You and me and the devil makes three,

Don’t need no other lovin’ babe,

Go to sleep little babe,

Go to sleep little babe,

Come lay your bones on the alabaster stones,

And be my everlovin’ babe.

Tobu Corporation, a giant railroad to real estate to department store combine that runs the trains into Kinugawa and holds considerable local clout, claims that “Kinuta statues are based on a tradition of placing lucky demons at important sites to ward off evil”, but to judge from the Japanese blogosphere, Kinugawa’s attempt to cuteify the demonic has not proven an unmitigated success, with one commentator mocking the obviousness of the Kinuta appellation and another saying that, being neither cuddly nor fearsome, the statuary falls between two stools.

On the stairway to Friendship Bridge, a giant demon has been set into the stair risers.

The walls to the right of the stairs are inlaid with a retro mural that must date from the late 1980s and harks back to the elegance of old-fashioned days.

The weightlessness of the winsome scenes and the soul-bereft blankness of the eyes of the castings induced vertigo, an old family vice, and led me to teeter on the devil’s staircase as I tried to photograph them.

Sitting down to regain composure, head in hands, I recalled for the first time in ages that I had passed through Nikko one spring day in 1987, just out of my teens. Had these somber revelers, with their bejeweled balls and umbrellas, already embarked on their journey of endless levitation on that day? And what did I remember of the visit? Nothing of the shrines and the temples, only running unplanned into a neighborhood festival, at which a drunken celebrant in happi coat clasped my shoulder, plied me with a can of beer, and insisted he pose with me, crouching in front of a portable shrine, for a photograph taken by his friend, a photograph that I had only glanced at perhaps twice in the last couple of decades but which I was sure still existed in an album buried deep in the basement.

Was I destined to remember nothing of these days in Kinugawa save the photos I took? Once home, I dug out the album, and was horrified to discover that nothing about the photo was as I remembered: I was not in the frame, he was not the ruddy-cheeked and squat salaryman of memory, but a more elegant and aloof presence in formal haori jacket, standing tall, and this was not some nameless neighborhood matsuri but the Yayoisai, the most elaborate of all in Nikko’s festival-crammed calendar and the harbinger of spring. A little research allowed me to assign an exact date to the photograph: April 17, 1987.

The photograph—or rather my mistaken recollection of the exuberance it expressed—had been instrumental in my decision to move to Japan in 1995. Had the last decade and a half of my life been some ghastly mistake, built on the quicksand of a memory of an epiphany now demonstrably false? Another, consoling, possibility unfurled: that it was the photograph that was lying and that my remembrance was of an event that had indeed occurred, temporally very close to the one in photograph, but which had not for whatever reason been recorded on film, or, if it had been recorded, had not made it to the posterity of the album for reasons of blurriness or bad composition.

And what of these—copious—photos of Kinugawa I was now taking? Where would they be two decades’ hence? Would they be the only aide-memoire left? Would they, unlooked at, turn as unreliable a narrator as my photo of the Yayoisai had proven? Would I have forgotten every detail that proved too technically demanding for the camera—for instance, the full-scale replica of a vintage motorcycle made entirely of wood that stood, just too distant for the lens, in the lounge of a hotel so freshly forsaken that I approached the entranceway with the intention of enquiring after the cost of accommodation, only to find the glass doors refusing to part and reception unpeopled.

************

Brooding on this, I tramped wearily up and down the streets, determined to inspect every last hotel. When Professor Ito talks of the ugliness of Kinugawa, he is referring primarily to the abandoned hotels: if we parcel out the resort into four quadrants, then all of the hotels in the northwest quarter have gone out of business, some many years ago. In the southwest quarter there have only been a handful of failures, while on the eastern bank almost every hotel remains.

The northwestern hotels fell victim to geography, built as they were on a sliver of land between the gorge and the mountains, and their attendant lack of parking space. In the daytime, from the faces they present to the river, the casual stroller might not guess that anything was amiss.

In the gloaming, they assume a more menacing mien, one that the professor, punning on Kinugawa’s name, describes as bloodcurdling or ghastly, (鬼気迫る—“with the spirits of demons closing in”).

The Kinugawa Kan, with its kappa water sprite baths, was, to gauge from the depth of its rust and the decay of its detritus, one of the first to succumb.

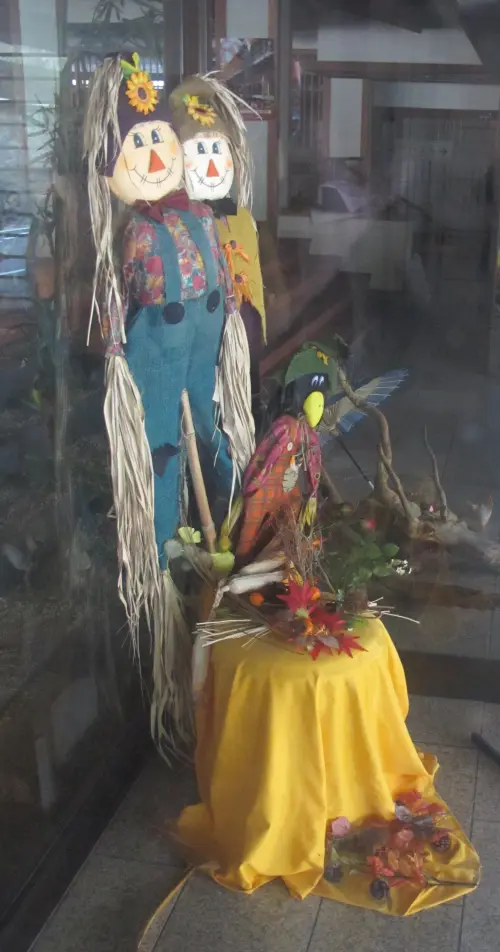

In the vestibule of the adjacent Daiichi Kinugawa Hotel stand Mr. and Mrs. Scarecrow and a piratical crow, dressed for an autumn festival that never came.

One moonless evening, I walked the almost untrafficked stretch of road on which these hotels stand, hugging the mountainside, staying as far from their gothic embrace as possible, when the headlights of a passing car picked out a slight woman in late middle age advancing toward me, scurrying up the hotel side of the street, her face, as she saw me, suddenly paralyzed in a rictus of fear. With my ghostly pale skin and long unkempt locks, I had for a moment become her demon of Kinugawa.

Elsewhere, hotels have been vacated less chaotically; in their lobbies, armchairs kiss unnaturally and dust collects traces of occasional intruders, but they feel as though they could be reopened with the flick of a switch—although they never will be.

A peeling sheet of A4 paper in the window of the latter’s lobby, dated 2005, thanks customers for their patronage down the years.

Ruination has shown no let-up in its encroachment: on the fringes of town, freshly delivered post piled up in the letterbox of Hotel Choju no Yu (“waters of longevity”).

I caught it in what may have been its first act of decomposition, as the weight of an unusually heavy snowfall had just brought down its sudare bamboo awning.

Professor Ito ascribes the building of the Kinugawa ghost town to the Bubble, but of course it is people—here, the independent hoteliers of Kinugawa, most with only one hotel to their names—and not bubbles that build. And what the hoteliers of Kinugawa, bereft of the revenue stream of a chain of hotels, needed more than anything was money—someone else’s money.

The Kinugawa branch of the Ashikaga Bank stands mute, giving away nothing of its role in the precipitous rise and equally precipitous fall of the town. The bank’s woes were the subject of a 2002 article in the (pre-Murdoch) Wall Street Journal that ranks to my mind as one of the best pieces of reportage on Japan of the last decade and which exists on the Internet now only in the vaults of a Pennsylvania university, so I thought I would pluck it from obscurity and hand over to the author for a while.

Many Ailing Banks in Japan Lean on Old Friends for Help

Local Ties May Only Delay the Inevitable As Tokyo Seeks to Weed Out the Losers

By PHRED DVORAK

Staff Reporter of THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

December 5, 2002

TOCHIGI, Japan—An official of Ashikaga Bank Ltd. late last year visited

the bamboo-lined campus of Kokugakuin University Tochigi here to discuss a

fund-raising drive. But it wasn’t the college asking for money. It was the

banker.

In Japan’s decade-long financial debacle, Ashikaga’s problems are typical:

a mountain of bad loans, a plummeting share price and rumors of impending

collapse. As the government preaches free-market reforms to fix the

system, ailing lenders such as Ashikaga are propping themselves up by

tapping healthy customers for funds.

The university was a good target. Kokugakuin Tochigi had $65 million in

savings in the bank. And four decades ago Ashikaga had lent the school

start-up money when nobody else would. “That’s why we exist today,” says

vice-chancellor Yoshinari Kimura, a square-jawed 70-year-old, who

remembers that first loan. In January, responding to the bank’s appeal,

the school gave the bank $2 million for new Ashikaga shares.

As Japan wrestles with a crisis that has cost banks $657 billion so far in

losses from bad loans, the government in Tokyo is starting to say that

market forces should be allowed to weed out the weak. Heizo Takenaka, the

new minister of economy and banking, is crafting a cleanup plan for the

country’s biggest lenders that could force them to be much tougher on

their borrowers than they are now. Those banks extend about 40% of all

loans in Japan and hold about half of all the bad debt. Some lenders might

be nationalized; big companies could go bust. Regulators also are hurrying

to shut down weak credit unions and co-operatives—to the distress of

the small businesses that borrow from them.

Overall, these changes mean cutting the complex ties that have bound and

preserved banks, corporations and communities since the nation’s postwar

reconstruction.

But in Tochigi prefecture and many other places, tradition and desperation

have produced an alternative survival plan: Customers with money to spare

are helping bail out their banks. And banks in turn are helping support

troubled customers.

In the past year in Tochigi, the mountainous region north of Tokyo where

Ashikaga is based, the prefectural government has bought $2.4 million of

shares in the bank. Camera maker Nikon Corp., which has three factories in

Tochigi, has pitched in more than $750,000 for the share-buying drive.

Other helpful investor-clients have included beauty salons and

pinball-machine makers, Toyota dealerships and department stores.

In all, Ashikaga has gotten $242 million of capital from 12,055 customers

in the past year—on top of a similar 1999 bailout that netted $345

million. Local governments and businesses own about 60% of Ashikaga, with

the rest held by big international companies and investors. Ashikaga

accounts for almost half of all loans and deposits in Tochigi prefecture.

The bank’s share of local lending is growing, as bigger banks retrench and

smaller financial institutions go under—six failed in Tochigi last year.

So far, the mutual-support strategy has been a short-term solution, and

it’s unclear how much longer it can work. After Mr. Takenaka, the bank

minister, finishes his plan for large lenders, he’ll try to fix smaller

banks such as Ashikaga. Meanwhile, some of the bank’s client-investors are

getting anxious, especially after a Japanese economic weekly recently

rated Ashikaga the nation’s second-most-troubled bank out of the country’s

125 lenders.

“We can’t have this kind of thing dragging on forever,” says Shintaro

Yoshizawa, president of a limestone quarry that has sunk $1 million into

Ashikaga shares since 1999. “but we’re all wrapped up with each other in

these extremely sentimental, tangled relationships.”

Almost all of Japan’s major banks and lots of smaller ones have

successfully hit up their customers for investment in the past five years.

Ashikaga’s biggest shareholder, the giant Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi, has

provided Ashikaga with a line of credit of more than $806 million for the

bank to use in case of emergency.

The banks are also working to keep afloat many of their own troubled

clients. Ashikaga has even found itself playing travel agent to drum up

business for struggling borrowers involved in Japan’s hot-spring spa

resorts. Some 80% of these spa borrowers are classed as loan delinquents.

“We are one with our customers,” says Kunihiro Ono, a manager in

Ashikaga’s planning department. “If our customers’ businesses don’t

improve, we’re sunk, too.”

The bank’s complex relationship with clients who are also shareholders

creates conflicts. At a shareholders’ meeting in June, irate investors

protested Ashikaga’s weak earnings, but as they were borrowers, too, they

also howled about a new campaign to boost profit by raising interest rates.

Prosperous Region

Ashikaga started out 107 years ago lending money to silk-spinners in

Tochigi and neighboring Gunma prefecture. Tochigi is now a fairly

prosperous region of two million, home to factories of some of Japan’s

largest companies, such as Honda Motor Co. After World War II, when money

was tight, the bank helped the national rebuilding effort with loans to

nearby municipalities. Town halls reciprocated by giving Ashikaga all

their business—from deposits to tax collection. As Tochigi’s economy

followed a nationwide trend in shifting to manufacturing from homelier

trades such as silk and rice, the bank’s importance as the major local

provider of funds grew. Today, Ashikaga is the official banker for all 49

of Tochigi’s cities, towns and villages.

In the prefectural capital of Utsunomiya, 75-year-old Kiyoshi Fujii,

chairman of building-materials vendor Fujii Sangyo Corp., notes some signs

of Ashikaga’s pervasive influence. Hanging on his office wall is an oil

painting of two mountains that an Ashikaga executive persuaded Mr. Fujii

to buy from another bank client. The Tochigi Industry Council, comprising

91 heads of the biggest local companies, is based on the fifth floor of

Ashikaga’s headquarters. Mr. Fujii, one of the community’s most prominent

businessmen, says he persuaded the bank to provide the space 25 years ago,

since most members were already Ashikaga clients anyway. “I said,

‘Everyone already does business with Ashikaga, and the guys that don’t—

we’ll just make them start,’ ” he recalls with a laugh.

But by the mid-1990s, Ashikaga was in trouble. Like many other lenders

near Japan’s big cities, Ashikaga piled into the real-estate lending boom

that trebled metropolitan land prices during the late 1980s—and was

flattened by delinquent loans when prices crashed in the 1990s. Shares of

Ashikaga and other weak lenders plummeted in 1997, after Hokkaido

Takushoku Bank, the biggest bank on the northern island of Hokkaido,

collapsed.

In the spring of 1998, Ashikaga got its first government bailout, a

capital injection of about $242 million at current exchange rates. But

that wasn’t enough. By early 1999, a crackdown on bad loans tied mainly to

the real-estate bust had driven Ashikaga’s capital ratio—the ratio of

capital to assets and a key measure of financial strength—to just a

hair above the 4% regulatory minimum.

Mr. Fujii and the Tochigi Industry Council rallied to Ashikaga’s support,

urging depositors to leave their money in the bank and heed the bank’s

plea to buy new shares. Tochigi prefectural officials also decided to

invest, disturbed by reports that bankruptcies in Hokkaido soared after

the area’s main bank failed. Other local municipalities and businesses

followed. Eventually, the national government pumped in $847 million in

capital.

Struggling Again

But two years later, Ashikaga was struggling again. Saddled with $723

million in bad-loan losses, the bank asked customers for another round of

investment. They agreed, although they decided to keep a closer eye on the

bank. Mr. Fujii got a seat on Ashikaga’s board. Local government officials

and other investors formed an oversight panel. In return, Ashikaga played

up its image as a generous creditor and promised to keep cash flowing to

local communities. The city of Utsunomiya, for instance, asked Ashikaga to

maintain its 80% share of lending to small businesses.

“If the customer has any ability to improve at all, we’ll support him,”

says Makoto Yasuno, head of the division handling defaulting or

restructured borrowers—renamed the “corporate-support division.”

One beneficiary is the hot-spring resort Shikisai, high in the mountains

in western Tochigi.

Located by Lake Chuzenji and the famous shrines of the

city of Nikko, Shikisai has a dining hall fronted by two-story plate-glass

windows, a pine-lined bathing room and 36 guest rooms. The resort was

planned during the boom years of the late 1980s, when busloads of office

workers packed local hotels. But by the time it was built with Ashikaga

money in 1996, Japan was well into a decade of stagnation that cut the

number of visitors to Nikko by 24% and the number of hotels by 20%.

Now, business is so bad that restaurateurs on a recent afternoon were

trying to snag lunch customers by hailing cars on the street. A more

down-market resort, the Palm Springs Hotel, still stands empty six years—

and six auction attempts—after it went bankrupt. Shikisai, which is

getting only about half as much revenue on its rooms as it had initially

planned, was passed to Ashikaga’s restructuring team three years ago.

Neither the bank nor the hotel will say how much Shikisai owes. But

hotel-industry insiders say it’s common for Japanese hotels to have so

much debt and so little cash flow that it would take them a half-century

or more to repay.

“I thought the economy would recover, so I built the hotel and failed,”

says Kazuhiko Kamio, Shikisai’s general manager. Glancing nervously at the

Ashikaga banker sitting next to him, he quickly adds: “Well, I haven’t

failed yet.”

For Ashikaga, it’s vital that Mr. Kamio and others like him succeed. About

half the loans by the bank’s Lake Chuzenji branch are to 15 big borrowers

such as Shikisai, which each have millions of dollars on the line. Ten are

handled by the eight-member team Ashikaga has set up to work out loans of

its hot-spring clients. The team actually serves more as financial

consultant and marketing adviser.

Mr. Kamio recently asked the team to help find a cheaper source of the

socks that top-end spas give guests to wear after a bath. Ashikaga found a

supplier that sold them for about 16 cents less per pair than Shikisai had

been paying, saving more than $4,000 a year. Ashikaga advised Mr. Kamio to

haggle with the local power company for cheaper rates. Mr. Kamio even put

beer bottles in the toilet basins so that each flush used less water.

Hiroshi Tsukahara, the Lake Chuzenji branch manager, pleaded with

Ashikaga’s loan department to lend Mr. Kamio new money to build six luxury

Suites—even though Shikisai had trouble paying back what it already

owed.

Recently, Mr. Tsukahara persuaded the president of a bridal-furnishings

store to spend a vacation at Shikisai. The president already banked at

Ashikaga, had received business introductions from Ashikaga and had bought

Ashikaga shares—and so she willingly obliged.

All this assistance delights Mr. Kamio. “Going to the bank is actually a

lot more helpful than fumbling around on sales calls,” he says.

Meanwhile, Mr. Kamio is hammering out his third business plan in three

years. He concedes that the last one was too optimistic, since it was

based on occupancy estimates of 2.7 guests per suite per night, even

though each suite has only two single beds. Still, Messrs. Kamio and

Tsukahara vow they can get the numbers to come out right and keep Shikisai

in business. Each man’s neck is on the line.

“If I don’t become a model for success, Mr. Tsukahara will be in an

embarrassing position,” says Mr. Kamio, looking sheepishly at the other

man.

“It’ll work,” Mr. Tsukahara replies firmly. “You’ll be one of the

winners.”

What an insane, topsy-turvy place Japan inhabited in the early years of the 21st century, with hotel managers drawing up business plans that defied the laws of physics and bankers borrowing from their clients instead of lending to them.

Ashikaga Bank limped on for less than a year after Mr. Dvorak’s article was published: when its auditors refused to sign off on its use of deferred tax assets, an accounting sleight-of-hand premised on future profitability that the auditors determined was an impossibility, for its fiscal 2004 first-half results, it fell into a state of negative net worth—more liabilities than assets—and was nationalized in December 5, 2003, with its shareholders, many of whom who were now vulnerable local businesses, thanks to the bank having gone cap in hand to its borrowers, completely wiped out.

There then ensued an interminable clean-up of nonperforming loans, recapitalization, and a hunt for a buyer. Foreign private equity houses reportedly sniffed around the rotting carcass of the bank but local hostility to such a sale was implacable, with the prefectural government repeatedly calling on the Financial Services Agency to rule out foreign bidders. Ashikaga Bank was finally sold to a group led by securities firm Nomura Holdings in March 2008 for just Y120bn (about $1.35bn), although what an investment bank with global aspirations wants with a failed regional lender like Ashikaga is beyond my ken.

And what of the rest of Mr. Dvorak’s cast of players? Kokugakuin University Tochigi continues to educate the youth of the prefecture and Yoshinari Kimura, now 78, has been elevated to chancellor. As a deeply out-of-favor two-year university, with just six faculties—Japanese literature, home economics, elementary education, Japanese history, commerce, and liberal arts—no crystal ball is necessary to divine that its prospects in its present incarnation must be bleak: 85 two-year universities across Japan have closed their doors to new enrolment over the course of the last decade, according to one source, although some merged with other higher education institutions and still others reinvented themselves as four-year universities.

Nikon retains its three factories in Tochigi, but there has been a huge exodus of manufacturing from the prefecture of late, according to Bloomberg: in 2009 alone construction machinery maker Komatsu closed a dump-truck assembly plant, precision equipment specialist Hoya closed the last Pentax camera plant in Japan, and consumer electronics giant Panasonic closed a fax-machine plant. One man interviewed for the article, recently made redundant, bemoaned the dearth of jobs:

“There isn’t anything out there,” said Yuuji Takashi, 53, who lost his job at a car parts-maker early last year. “They’re sending it all to China.”

Building material supplier Fujii Sangyo remains in business, although Kiyoshi Fujii has handed over the reins to son Shoichi. Sales dropped 9.0% in FY3/09, another 13.4% in FY3/10, and the company fell into the red; the share price is back below where it was a decade ago.

Hot-spring resort Shikisai soldiers on, although it was deserted when I dropped by and the “dining hall fronted by two-story plate-glass windows” was a demure letdown; I had been hoping for something much more gaudily Bubblicious.

************

As visitors to Kinugawa Onsen melted away, so the amusement facilities that had sprung up to cater to their holiday spirits fell on rockier times. Western Village, a Wild West theme park, some of whose structures were built as late as 1995, gave up the ghost in 2007.

Shorn of its sign, the post and crossbeam at the entranceway looks ominously like a gallows.

Weep on your tears of rust, oh cowboy, for nevermore shall you give a gunslinger’s welcome to the holidaymaker hordes.

The park had been secured fast from the front but it was possible to sneak pictures through gaps in the stockade.

Westworld: where nothing can possibly go wrong. Boy, do we have a vacation for you!

The building behind the church bears a signboard proclaiming “The Legend of Little Snail”, which has defied all attempts at elucidation and will forever remain a mystery.

Sheriff Spirits, a shot bar in the shape of a bison with motorized underpinnings. The Bubble made anything and everything make sense.

The Rodeo Coffee Shop, Silver Spur Saddlery, Saloon Longhorn, and a nameless bank circle the rotting concrete stands where spectators once watched western shows. I started to hum an old Theater of Hate tune.

The yellow sun was setting in Tombstone,

The citizens were gone but not to their homes,

By a freak a coin in the piano made it play,

But only the wind and the dust heard it say,

“Do you believe in the Westworld?”

Around the back, a tiny public thoroughfare splits the park apart, allowing access to some of the attractions.

Laser guns this way.

From the south on a wind in walked a cowboy,

The saloon was dry but his guns were well oiled,

Somehow he remembered when he kissed his wife,

And when he said goodbye,

But that was before the circus with the bear arrived,

Oh, the bear it roared as the gun was fired,

Then the cowboy turned the gun on himself as he sang, “Noone’s alive”.

My real quest was for the greatest relic of them all, one I remembered well from passing this way a couple of times a decade or so before, but which was now all but hidden from the main road by a phalanx of fast-growing cypresses. Off I strode through a snow-dusted field of bamboo grass.

Snagged, the money shot! Mount Rushmore on Kinugawa, hewn from finest concrete, with black mold taking hold. What Mount Rushmore, located in South Dakota and completed in 1941, has to do with the Wild West is a riddle only the creators of Western Village can answer. What disturbs me most about the Kinugawa Rushmore, which is as large as the original, are the wild, staring eyes of Thomas Jefferson, quite unlike the beatific expression sculpted by Gutzon Borglum. Was the Kinugawa crafter a revisionist historian?

The surroundings might be said to lack the grandeur of the Black Hills.

The crossroads on which Western Mura stands are a perfect trifecta of desolation. On the far corner lies the New Riraku Hall, oddly named even by local standards, which seems to once have been a noodle joint.

Opposite, weeds wither in the cracks of the Parlor King Palace parking lot.

In the Nikko area, there are many more abandoned pachinko parlors than there are surviving; central Kinugawa’s only parlor is long gone.

Around town, unremoved signs speak of Wannyan Mura, perhaps best rendered as “Doggie and Pussy Village”, a theme park that promised, the signs say, a convocation of 600 dogs and cats of different breeds from around the world.

You can see! touch! play! Even by the debased standards of the Bubble, this is desperate stuff. You want me to pay to enter your glorified pet shop? I knew Wannyan Mura had gone under in 2008 but I hoped some trace of it survived, so I followed the instructions of the latter sign and drove straight on for 3.3km. Circling and circling again, I found no remnants, and stopped to ask at one of the few remaining roadside booths that had been set up in Bubble times to arrange accommodation for tourists heading into Kinugawa; almost all of them are derelict now.

“I’m looking for the site of Wannyan Mura.”

“Oh, Wannyan Mura went bust,” she said cheerfully.

“Yes, I know. I was just wondering if any of the buildings remain.”

“Oh no. They tore it down beautifully. Leveled it, they did. It’s beautiful now.” Kirei ni natta.

If only I knew what those three words really mean. Many’s the time I’ve heard them, as Japanese men and women of a certain age have gazed out on some hideous cityscape or despoiled rural vista. Maybe I do know but am too scared to acknowledge it: they mean that order has been restored, dominion over the natural world has been reestablished, and all traces of the shambolic wrong-turns of the past have been eviscerated. I would rather live, most of the time, with the memento mori of failure.

She kindly gave me directions to where Wannyan Mura had stood, behind a Yakult depot; the land had indeed been leveled, and parceled out for detached housing, although there had been no takers. Beautiful it was not. I dread to think what happened to the dogs and cats.

Billboards also remain scattered across town for a giant labyrinth, which the official Kinugawa website describes as follows.

Don’t you want to challenge yourself in the Grand Maze as big as 3500 square meters? Do you plan to enjoy the walking while exploring the labyrinth or try to break the record of using shorter time to find way out? Come and enjoy it with your family and friends on the way of rushing out!

Hmm… The brooding conifers, the brightly painted guard towers at each corner, the impossibility of escape… It was a Legoland concentration camp.

Conscious perhaps that a grand maze would not cut it as an attraction on its own, the creators had tacked on an Astroturf putting course.

Inside the maze, a sensory horrorshow of flimsy fencing and unforgiving asphalt. In the delusion of the dreams that inspired it, the desperately pinched budgets behind its construction, and the almost certain financial ruin that accompanied its closure, the grand maze was for me the single most dismal location in the whole of Kinugawa.

Some of Kinugawa’s more minor tourist venues, such as the 3D Museum of Cosmos and Dinosaur, struggle on, although it’s apparent from their fading paintwork, aura of neglect, and deserted parking lots that, for many, the end cannot be very far away.

Through our visual and acoustic effects, tourists will feel like traveling across the time and space to the world of microcosmic insects and mysterious dragons in the distant Milky Way. The Museum consists of Cosmic Theatre, Insect Theatre, Dinosaur Theatre and Insect Museum, an amazing place to be stunned and moved.

As Kinugawa’s hotels have surrendered to their fates, cooks and dishwashers, bedmakers and waitresses, cleaners and receptionists have departed, rending gaping holes in the town’s infrastructure.

With the closure of Uotatsu, Kinugawa was left with a solitary supermarket to serve its inhabitants. Much has been made in the media lately of the phenomenon of food deserts, in which town-center grocery stores close down or move to the suburbs and the car-less elderly and infirm no longer have ready access to sources of fresh—or indeed any—food, and in this respect Kinugawa is a Sahara: while many other rural Japanese towns of its size still retain mom and pop grocers in their centers, in Kinugawa they were long ago muscled out by the hotels.

************

With the demise of Western Village, Kinugawa was left with two marquee crowd-pullers: Edo Wonderland Nikko, an elaborate but pricey recreation of life in the Edo era (1603-1868), which survives, I suspect, because it is deemed just educational enough for school excursions, and Tobu World Square.

The English-language leaflet says:

Tobu World Square is a theme park exhibiting world-famous architectural works and ancient monuments, all scaled exquisitely down to 1/25. Feeling as if in a museum of architectural structures, you will see a total of 102 structures from 21 countries, including 45 inscribed as World Heritages by UNESCO. You will feel closer to the daily lives of the world.

Tobu World Square would be more accurately named Tobu Japan versus the World Square, or simply Tobu Japan Square, as nearly half—47 out of 102—of the structures are located in Japan, and the park has much more to say about the worldview of official Japan, circa 1993 (not greatly changed from the worldview of official Japan in 1980 or 2010), than it does about “the daily lives of the world”.

The visitor experience is tightly corralled, orchestrated by signs that demand you move this way or that way. The starting point is the modern Japan zone: modern Japan is taken to be synonymous with Tokyo, as all of its dozen or so recreations, such as the Diet building and the Yoyogi National Stadium, are located in the capital. At Narita Airport’s Terminal 2, planes taxi interminably without ever taking off.

The zone’s prime attraction, though, is its newest arrival, Tokyo Sky Tree, a digital terrestrial TV broadcasting tower which, at 634m on completion in late 2011, will be the world’s second tallest freestanding structure after Dubai’s Burj Khalifa.

Even the 1/25th reproduction is as tall as an eight-storey building, lording it over the Eiffel Tower deep in the background and the still-standing twin towers of the World Trade Center. The message is unambiguous: Japan is still number one, at least within the fantasy realm confines of a theme park. In a case of art—or perhaps artifice—imitating life before life has even had a chance to breathe, the model was topped out and opened to the public this April, a full two years before the real tower opens, its unveiling attracting front-page coverage in the national press. (Perhaps it was a slow news day. But then every day in Japan is a slow news day). A surreal self-referentiality stalks the air, as the developer of the real Tokyo Sky Tree and the owner of the theme park are one and the same, the mighty Tobu Corporation, and indeed most travelers to Kinugawa by train from Tokyo will pass the real thing, still under construction, shortly after setting off.

From modern Japan, the visitor is conducted past a stretch of water that must be taken to represent the Pacific, the Atlantic, and a good few more of the world’s seas oceans straight to New York, the cultural capital of The Only (other) Nation That Matters, and indeed the only other nation privileged with a present, in the form of recognizably modern architecture, as well as a past—albeit a shallow one in the shape of a solitary structure, the White House.

The events of 9/11 must have caused the planners of Tobu World Square an anguishing dilemma: tear down the twin towers and diminish the impact of the voyage from Japan to the anti-Japan, or leave them standing and invoke a certain dissonance in the minds of the voyagers. They chose to leave them up—another awful warning of how dangerous the world is beyond Japan’s tranquil shores.

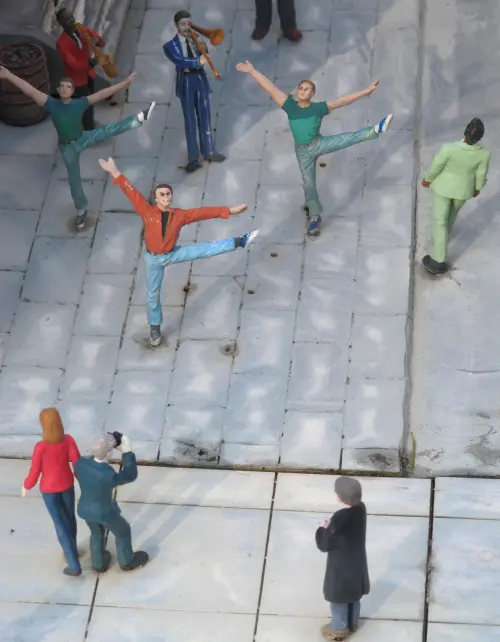

While most of the street-level scenes in the rest of the world are blandly generic ones of inchoate masses milling about, attention was lavished on New York.

Fame! I wanna live forever, I’m gonna learn how to fly!

While the Big Apple is granted a measure of vibrancy, the careful observer of the street is left in no doubt that New York is a hotbed of crime, collision, and chaos.

It’s enough to make the intrepid adventurer turn tail in a heartbeat and flee back to the safety of Japan.

There follows a brief excursion through Egypt—sub-Saharan Africa need not apply, nor for that matter need Central or South America, Australia or Oceania, or the Middle East, as whole continents have been airbrushed from the Tobu world. Every single structure is north of the Equator. Hemispherist!

The visitor then pitches up in Europe, home to so many castles, palaces, and cathedrals, and which is allowed more structures—32—than anywhere save Japan, although none more visibly modern than the Eiffel Tower.

Some have lauded Tobu World Square for the faithfulness of its architectural replication, an example of the delight in attention to detail and adoration of miniaturization purportedly inscribed in the national DNA—think bonsai or netsuke. Certainly, the big set-pieces such as St. Peter’s Basilica do inspire a modicum of awe.

Even the most fervent architectural geek would find it hard to comment on the accuracy of the gargoyles of Barcelona Cathedral or the Milan Duomo. Down at street level, though, something had gone awry. What, for instance, is the black prewar Citroen doing lurking in the background of the New York pile-up above? The planners had bought a job lot of VW microbuses from the 1960s—they were everywhere—and later, another job lot of new Minis.

A Routemaster advertises that food beloved by Dracula-hunters, stake and kidney pie, and carries an enigmatic sign that reads, “Boys, fly! I will never forget you!”, sentiments that have assuredly never graced the side of a London bus.

Far too many of the little people were clad leprechaunishly either partly or wholly in green and many had tilted one way or another down the years, giving the viewer the impression of dizzying mass inebriation, perhaps, or that the promenaders were being buffeted by their own personal whirlwinds.

With time and space, perspective and proportion all having collapsed, I was seized by another fit of vertigo and had to sit down and rest awhile, eyes averted from tower and temple, pyramid and villa. I recalled that in the summer of 1995, within a month of arriving in Japan, I had been orchestrating (to call it “teaching” would be grandiloquent) an evening English conversation class with a bunch of employees of the No. 82 Bank. We were talking of travel, and I asked one of the younger ones—let’s call him Shin—whether he had ever been abroad. “No”, he replied with pride, “I am 100% junsui pure Japanese!” Aha, I thought to myself, we are dealing with the flower of a national identity so fragile that it is possible to conceive of it being scythed down by a footstep trod in a foreign land.

Shin’s comment has gone on to explain much down the years, from the inability of Japanese teachers of English to speak the language they teach (because the Ministry of Education will not make a year overseas mandatory for all undergraduate students of foreign tongues, lest they are contaminated and go native) to a comment I overheard just the other day, made by one youngish Japanese woman to another, “I love Korean food so much it’s as if I’m not Japanese!” Nihonjin ja nai hodo Kankoku ryori daisuki desuyo. Try replacing “Japanese” in that sentence with your own nationality and “Korean” with your own favorite foreign food and savor how outlandish it sounds.

Tobu World Square, then, is the perfect solution to Shin’s unposed dilemma: how to experience, if not engage with, the foreign other while maintaining complete control, with nothing more to fear than a spilt ice-cream. Much the same can be said for Japan’s myriad single-nation theme parks: British Hills, perched on a mountaintop in the backest of Fukushima beyonds, the three mura villages scattered across Japan devoted to New Zealand, and the most gargantuan—and most troubled—of them all, Huis ten Bosch, a replica of an entire Dutch town on an island near Nagasaki, to say nothing of those treasures we have lost, at their best their names a delirious marriage of a provincial Japanese locale and a foreign nation of implausible interest: Kashiwazaki Turkey Culture Mura and Niigata Russia Mura, to name but two.

Many have fallen by the wayside, which the optimist in me would ascribe to disenchantment with the manufactured and manicured nature of the experience, the pessimist in me would attribute to sapping interest in anything foreign at all, and the realist in me would lay at the door of the Bubble resort boom and its sorry aftermath. I whipped through the Asia zone, and after returning to the comfort of the pavilions and pagodas of the traditional Japan zone, left Tobu World Square at the tolling of the closing knell, only to be greeted by the same taxi driver that had deposited me there an hour before. Business was so bad he had chosen to wait rather than cruise the streets of Kinugawa in fruitless search of a fare.

************

Kinugawa had one last secret to spill, and as a guide to it I shall invoke the services of the incomparable chowchow, whose website, How to Walk of Japan, has been put through a machine translation wrangler so primitive and yet so sublime that it renders a description of the okapi, a giraffid even-toed ungulate, as a “rare hoof division giraffe department”, and which contains the sole other reference on the English-language Internet to my quarry, the Kinugawa Hihoden.

Kinugawa Hihoden is an example of what are more generally known as hihokan: what blunt Anglo-Saxons would dub a sex museum, what more romantically inclined French might label a musée de l’érotisme, and what Japanese, with a certain penchant for euphemism, call hihokan, (秘宝館, a hall of secret treasures). What follows is likely to be NSFW, not safe for your workplace, and as chowchow advises, “please refrain from a person weak in a sexual topic” from venturing any further.

The casual taker of the waters at Kinugawa would in all likelihood have no idea of the existence of the Hihoden: it stands a few kilometers north of town, up in the hills, there are no hoardings advertising its presence in the town itself, and there is no mention of it on Kinugawa’s official website; such prurience helps give the lie, perhaps, to the old Orientalist myth of Japanese concupiscence.

To avert any sense of shame, chowchow suggests that the embarrassed visitor could pretend to be dropping in at the convenience store that shares the parking lot and then divert to the Hihoden; sadly this ruse no longer works, as the convenience store has failed and has been boarded up.

The sign on the roof proclaims the Hihoden to be a resource center for the mores of Shimotsukenokuni, the old name for Tochigi Prefecture. Amazing, I thought to myself, does this mean there were sexual practices peculiar to Tochigi in the olden days?

A Noh mask and the face of a tengu goblin adorn the wall by the entrance. Like the oni demons of Kinugawa, the tengu is an ancient Chinese import and ambivalently a force of both good and evil, one that was transmuted from its original incarnation as a heavenly dog, first into a monstrous hawk with a human face and then into its current anthropomorphized form as a red-faced creature with a prominent nose.

An Edo courtesan solicits lucky coins inside the entrance. Chowchow advises that it costs Y1,800 (about $20) to get in, but the sign by the ticket booth saysY1,500. A man who, following chowchow, I’ll call Uncle, his face invisible behind frosted glass, pushed a discount coupon my way.

“Here, use this. You can get Y300 off.”

“Why, thank you,” I replied, pushing it back.

“Oh, let’s call it Y1,000 then. We don’t get many foreigners.”

“Well, thank you very much.”

Uncle was obviously the owner; no employee could have been given the authority for such spontaneous generosity. And although chowchow warns that, “unfortunately, Kinugawa Adult Museum is photography prohibition”, Uncle invited me to snap away. How could I resist such a kind invitation?

On the stairs, the tengu is getting it on with the Noh mask, his nose now a phallic proboscis, her mouth now a vagina.

Note the tall, one-toothed geta clogs that are characteristic tengu footwear.

The lucky penis and vagina are described as onadeishi (お撫で石, honorable rub stones), a term so obscure it gets only about 500 hits. I had entered the land of the outré.

The visitor then trips a sensor that triggers a curtain of water to fall on a dim tableau; after the rain ceases, holographic male and female demons cavort in a dance that possesses both kitschiness and a strange, subdued eroticism.

A sutra-chanting Buddhist priest of the Tochigi branch of Nara’s Yakushiji Temple dreams of intercourse, and gets a discreet mechanical erection beneath his robes.

A local warrior on the eve of battle, his lover alternately exclaiming that she is about to orgasm (“iku”) and imploring him not to go to war (“ikanai”), making the hoariest pun in the lexicon.

The crown prince bloom in profusion illusion dream, which can be called the greatest eyeball. It is a general of time, luxurious 5P of Hideyoshi Toyotomi [1536-1598, one of the key unifiers of the nation]. He plays against four women in the right hand, the right foot, the left foot, the sexual organs and once while holding a cup with the left hand. Because I am a stunt, I increase.

The animatrons took a darker, more rural turn, and I hastened on, into a room that recreates the erotic carvings of Khajuraho.

Suddenly emerging into bright light, the visitor is confronted with a series of panels drawn from biology textbooks picturing the male and female reproductive organs in clinical cutaway.

There is something joyously dated about the butterflies and profiles.

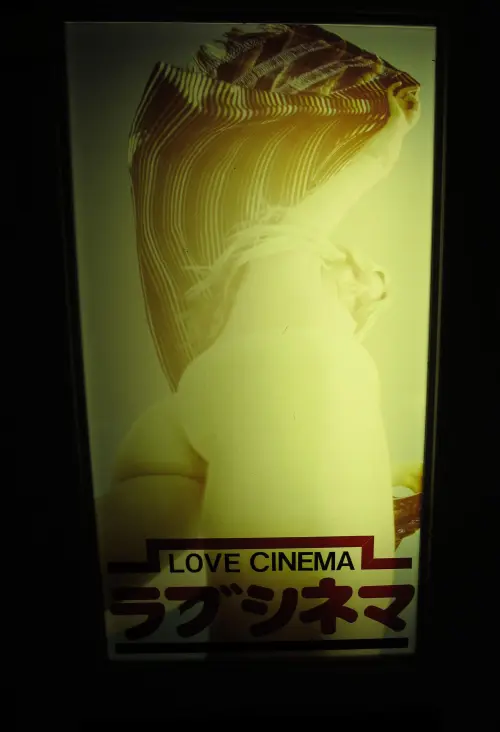

Descending the stairs, on the right comes the Love Cinema.

Rows of tiny white bucket seats, bolted to the linoleum, were the only observers of the scenes unfolding on the screen, as pairs of female mannequins in lingerie from the ’70s stood sentry to either side and an ancient mid-aisle projector wheezed on. Up on the screen, a pinku eiga softcore porn flick from the ’80s, drained of color almost to sepia, played to no one but me. A bored-looking woman extinguished a cigarette in a glass of water and began making desultory love on the floor to a man in a thong in a featureless room.

Dazed, I stumbled out into the glorious hodgepodge of the gift shop, where a blonde bombshell reclined on a couch.

A mannequin poses next to a shunga erotic print from the Edo era and a seductive kerosene heater.

Besides a selection of mildly tawdry sex toys and videos, there was a smattering of more eccentric gifts on offer: how about a piece of driftwood shaped like a penis with tiger markings?

Yours for only Y5,000 (about $60). Adjoining the gift shop was a tiny game arcade; most of the machines were out of order.

The walls were decorated with photos of trees whose gnarled trunks were supposed to resemble vaginas or—still better—penises entering vaginas.

Not a soul stirred. Pressing the buzzer on the counter, I summoned Uncle.

“Do you mind if I take your photo?”

“No, not at all.”

And with that, Uncle, while leafing through a men’s magazine in which he had recently featured, opened a box containing a dildo

and strapped it to his head, transmorphing into a human tengu of this river of angry demons.

“It’s just a bit of fun, isn’t it?”

“How many years have you been going?”

“Ooh, about twenty. There’s just us and the one at Atami left.”

“What about Beppu? I hear they have a museum like yours, too.”

He seemed not to hear.

The first hihokan opened as late as 1971, according to one source; Wikipedia lists 45 as having been in existence at one time or another, most at hot spring resorts, with just 21 left—fewer, I suspect, if the entry is even a couple of years out of date. No doubt Kinugawa Hihoden will be lost to posterity when Uncle hangs up his dildo straps.

What accounts for the meteoric rise and fall of the hihokan? They flourished as group tourism boomed, and as group tourism waned, so did they. While it is possible to imagine that a holidaymaking busload of earthy and lusty assembly-line workers, swigging beer from breakfast on, would have a great giggle at Kinugawa Hihoden, it is not a place any male saner than, say, Travis Bickle, would feel comfortable taking a date or his family. A society now super-saturated with sex and increasingly, some commentators claim, bored by it must also be responsible; while Japan’s “herbivore” men, more interested in waxing their legs and doing their nails than in worshipping the vagina and practicing Tantric sex, may be a media creation designed to sell books and launch TV careers, there remains to my eyes a kernel of truth inside the balloon of hype. But I would be remiss if I didn’t ultimately finger—yet again—the sweaty collar of demography: in 1971, Japan was a young nation, with scarcely 5% of the population over 65; as I watched the check-in theatrics at several Kinugawa hotels one afternoon, it became clear that the bulk of the in-checkers were in late middle age or the early years of retirement, cohorts not known for rhapsodizing over, say, the rutting cows, horses, and deer that feature at many a hihokan.

Chowchow awards Kinugawa Hihoden a “What’s cool” rating of 80%; I would give it 120% if I could. Let chowchow have the parting words as we take our leave:

I have told you a good thing for a long time now. … “When a good thing entered by the dozens, it and bought it and bought nothing because I was profitable,” the aunt said. Though the aunt of a stand invited you brightly, saying get and what on earth will be anything.

************

Our tour done, I return to Professor Ito’s assertion to ask, is Kinugawa truly ugly? What is ugliness is as profound a question, if less commonly addressed, than its correlate, what is beauty. For this observer at least, it is the living hotels of Kinugawa that are ugly, in their Bubble greed and vanity and hubris. The dead hotels have, in death, been forgiven the sins of their lives and passed into a sphere beyond the standards of beauty and ugliness that regulate the mortal world.

Seen at their best, on a soft spring-lit afternoon, the intricacy of their gradations, their sheer layeredness, evoke another time, another place—they could be a medieval village clinging to the ramparts of some Gormenghast-like castle, or a miniature Machu Picchu in the making, awaiting their Hiram Bingham centuries hence.

What else about Kinugawa is ugly?

Concrete, meet mountain. Mountain, meet concrete.

In the center of town, vestiges of buildings with doors to nowhere.

Almost directly opposite this refined hotel entranceway, a house implodes.

An abandoned town-center house, requisitioned for recycling duties, spews forth trash.

A dormitory for itinerant hotel workers, one of many that defile the town.

The hotels present their best faces toward the gorge; the wanderer around town is presented with their guts.

Rickety bungalows in the Kinugawa backstreets where tourists never tread: I lost count of the broken window panes that had been patched with duct tape, a sign of poverty if ever there was one.

The wasteland of Kinugawa Onsen station plaza, remodeled only three years ago in a crime of urban planning. The station is used by only around 3,000 people a day, fewer than 200 an hour, so an expanse this bereft of intimacy is bound to appear devoid of life at the busiest of times.

It was wandering the backstreets of Kinugawa that I came to appreciate that there exists a kind of Möbius strip of beauty and ugliness, a strip with only one surface and one edge that embraces both, on which a line drawn along the seam that starts at beauty arrives at ugliness on the other side, even though there is no side, before returning to beauty again. The following pictures need no other explanation.

Toward dusk on my last night, I was investigating whether a roadside soba restaurant had expired (it had), when I tripped on nothing, stumbled, and fell onto asphalt and gravel, gouging a hole in my knee. The demons of Kinugawa had their revenge. Back at the ryokan, I staunched the flow of blood as best I could with a tightly knotted hand towel and set off in search of food. Time was dragging on and Kinugawa is an early closer of a town. At a deserted pizzeria by the station, I asked if they were still open. “Yes, but you’ll have to hurry. Last orders at 7.30.” I ate amid deep silence, a rivulet of blood trickling down my shin and spilling, congealing, onto my sock. Determined despite everything to make one last circuit of town to take its Saturday night temperature, I hobbled off.

Snack Casablanca was draped in gaudy neon, blinking on and off, but no sound emanated from inside. Inside Bar Arizona, a bartender wiped glasses that no one that night would use. At Karaoke Pub Roppongi, there were no takers for the microphones. The names gave off silent screams: “please, please, anywhere but here”. While the hotel parking lots were full, the streets were lifeless barrens. It was as if humanity had given way to a higher, mechanized intelligence, or a neutron bomb, designed to kill all the living but leave structures intact, had exploded nearby.

Too disconsolate to raise the camera, I trudged back to the ryokan and sat on the steps for a while. Eventually, two drunk men shod in geta clattered past, arguing. Silence set back in. From nowhere came an unearthly clanking, a wooden spoon banged inside a witch’s pot; it turned out to be another geta-shod man, echoing down an alley. Silence returned. It turned 9.30; I had been sitting there a full quarter hour.

Back in my room, I downed a can of beer while staring out of the window onto the railroad tracks, the silence from time to time interrupted by the screech of trains lumbering up the valley without a single passenger, their rectangular pills of light an affront to the night, a ghost town’s ghost trains rattling their chains.

In bed, I bled slowly onto the crisp white sheets of the futon, fitful sleep tormented by a solitary mosquito, its proboscis a demon’s club or goblin’s nose, until by dawn Kinugawa, everywhere and yet nowhere, had collapsed in on itself in my mind and vanished, like a nightmare drenched in sunlight.

Fantastic post, as usual! Thanks so much for sharing! Ironically I was in practically all the places you describe at one stage or the other, but they were all open back then…(like the western village) and soaked in some of the ugly onsen hotels in their more glorious time…

I am more surprised that the Hihokan is still open, I photographed it already 3 times. Its fun, but not as impressive as Japan’s first Hihokan, which closed a few years back…lucky me had the chance to see it just before it closed down and it felt like time travel. If you click the link above, you can see them. I say only 3 disemvoweled words: Rttn Whl Vlv 😉

Again, fantastic writing here! More, more!

Juergen, thank you so much for getting in touch! I am a huge fan of yours! Please allow me to mail you properly in the next few days. All the best, R

Thanks for this – I really enjoyed reading it, and I think it’s your best post yet.

There must be hundreds of onsen towns around Japan that are tottering on their last legs. I haven’t been to Hokkaido, but it seems to me that a lot of the vacation-related building in Honshu was the result of a combustible mixture between the craziness of the bubble and the national obsession with winter sports during the ski boom.

But at least some of those onsen towns lucky enough to be bordering ski fields may have a chance of a revival if they can swallow their pride and attract wealthy skiers from places like China (they’re big ‘ifs’ for so many reasons)…but places like Kinugawa seem to have no hope .

Kinugawa is indeed a nightmare drenched in sunlight! The land that time, though not hell, forgot. Thank you for those photos – they are brilliant snapshots (no pun intended) of Japan`s future. The decay of Kinugawa seems especially advanced though, despite its proximity to Tokyo. It`s amazing to see how much nature has reclaimed in the space of less than two decades. Imploding houses and collapsing love hotels… What will be left by 2020? I imagine there will be some very confused archaelogists a couple of centuries later trying to figure out the Legend of Little Snail. That maze looks like the bastard child of Auschwitz and Hello Kitty.

I love the abandoned love hotel pics but you were lucky not to pick up tetanus in there!

One thing – while Wannyan Mura has passed into history, it does have a few younger relatives in Tokyo itself – there are cat cafes in Kichijouji, Shinjuku 3-chome and Ikebukuro that appear to be doing a roaring trade.

In a way, Kinugawa`s huge empty hotels seem like a bit of a waste – they could at least be an instant solution to Tokyo`s homeless problem. But I don`t imagine the good citizens of Kinugawa would be thrilled by the prospect.

I haven’t yet read all your posts, I don’t think I could handle that much reality all at once, but I just want to make sure you know how much I enjoy your writing and photography. I’ve only been here for a few years, and I’ve gotten around a bit, Hokkaido and some poor derelict Onsen towns outside of Kanazawa, but I will never look at this kind of thing the same way again.

Oh, and I learned a new word from you today, “conurbations” if you must know 😉

Great article again with some great photos. We wandered around the area a couple of years ago, wasting our money at Edomura along the way. One local regaled us with many stories of what the area used to be like pre-bubble. Western Village apparently used to even import Americans to work there and give it a bit of authenticity.

It certainly did:

http://blog.juergenspecht.com/2009/the-cutest-request-i-ever-received/#more-785

It is great to go through your stuff. I’m looking forward to more.

Thank you!

Incredibly thorough post! I would (and will) break this content up into many smaller chunks. Just swung by the Western Village recently- true that Mt. Rushmore has little to do with cowboys, but the owner of the place was (apparently) just so taken with the original when he took a highlights tour of the States (way back in early 90’s) that he had to replicate it in his long-standing ranch. Presto, $27 million replica.

I like the way you toss in bits of songs, other articles, poetry to your posts. Adds poignancy. Though I’ll dispute you on which locations provide the most poignancy. I’d go with theme parks- even more than love hotels they were places of life, laughter, and light; whole families coming together to just have a grand time. Those places now empty and fading, damn, that’s the one-step-removed-nostalgia hit I crave.

Aha, the legendary MJG… I’ve long been an admirer of your tales from the crypt at mjg.com although you might not be too taken with the collaborator at my latest post… Thanks for the additional tid-bits about Western Village; do you know what has become of the owner?

We’ll have to cordially agree to disagree about which offer the greater poignancy, love hotels or theme parks, although what I wrote was really only a rhetorical flourish and not a belief I’d stake my life on…

Oh man! I know this is an old post, but I had the privilege of taking a little driving tour of these ghost resorts a few years ago and was, well, haunted by them. Thanks for writing this, I always wanted to know more but probably won’t go back in this lifetime.

Also, this weird freaking place on the shore of Lake Chuzenji https://www.flickr.com/photos/mr0grog/15282462172/in/photostream/

Perhaps I need to read more than just this post but your tone is incredibly condescending and patronizing.

Pingback: Giappone in rovina: alberghi abbandonati a un paio d'ore dalla capitale - Il blog di Jacopo Ranieri